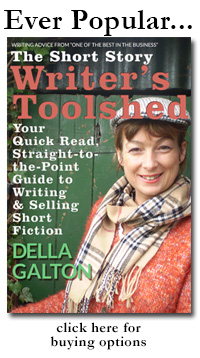

The Short Story Writer’s Toolshed was first published as a series in Writer’s Forum. I later decided to compile it into a handy little book. Here is an extract I thought you might like.

How The Toolshed Works

Every writer has certain tools at their disposal. We all in fact use the same tools when it comes to writing short stories, but we’re not necessarily that adept when we set out. This book is a little like an instruction manual, which I’m hoping might save you some time.

So, what exactly do we have in our toolshed? Well this particular toolshed is divided into shelves and on the shelves you will find the following tools:

Shelf one: ideas and getting started; shelf two: plot; shelf three: characters and viewpoint; shelf four: dialogue; shelf five: structure; shelf six: time span, pace and theme; shelf seven: flashback; shelf eight: cutting and editing; shelf nine: putting it all together; shelf ten rejection and motivation.

If you like you can work through the entire toolshed, or you might prefer to go straight to the relevant shelf. But to begin let me take you on a whistle-stop tour of the toolshed. Let’s examine what a short story actually is, as well as having a quick look at some of the available tools.

A Look Around The Toolshed

What is a short story?

This might seem like an odd question to ask in an ebook for writers. We all know what a short story is, don’t we? It’s a story that’s short; it’s less than the length of a novel; it has a beginning, middle and end and gives the reader the chance to spend a brief time with some interesting characters. Simple enough, you might think. But actually no, it’s not that simple at all.

It’s shorter than a novel, yes, but there’s so much more to writing a successful short story than size. The techniques used, the tools if you like, are exactly the same as the tools for writing a novel. Except they are used differently!

In this ebook which I hope will be useful to both beginners and more experienced writers alike we will look at how to use the tools we have at our disposal.

We will look at not just what makes a story work, but also examine the reasons why some stories which on the surface have all the right ingredients don’t work.

To my mind, writing a short story is like painting in miniature. It should have all the depth and colour that a full size canvas allows, but there is no room for waffle. Don’t make the mistake of thinking they are easy to write. Many successful novelists will tell you that short stories are one of the hardest forms of writing. They are a craft.

Length

The length of a short story changes with the fashion. If you are writing to sell, then your market will dictate what length you should aim for, be it magazine or podcast or radio. If you are writing for a competition then the rules will dictate the length. Even if you are writing for your own pleasure and have no desire to see your work in print, it is wise to set yourself a word limit. This is because length is relevant to the elements of a short story. For example, you’ll have trouble writing a story of 1000 or 2000 words if you have a cast of ten or twelve characters.

They’ve got shorter than they used to be. A quick search of the internet will reveal short story competitions that start with a length as short as 60 words. In fact, I even found one which had a word limit of 6 words. But most short story competitions these days have a maximum word length of around 5000 and this is probably on the long side. The vast majority of competitions ask for short stories of between 1000 and 3000 words.

Magazine lengths are similar. Podcasts may go a bit longer. So even if you are not setting out to place your work, then it might be as well to limit yourself to a saleable length just so you can get into the feel of writing something shorter. If you find your stories feel stretched at 3000 words then you might want to reduce it, but the best way to find out is to write a few. See if the pace suits you. Find the length you are comfortable with and then stick to it until you feel you have mastered the art of fitting your plot and characters into that space.

Characters

You won’t have room for dozens of characters. In my experience one or two main characters are usually enough. You may of course need supporting characters, but look at them as bit part characters who don’t necessarily need to be fully developed or even named. That doesn’t mean they should be stereotypes. There are many ways of making minor characters spring to life with very few words.

We will look at this in more detail when we get to characterisation. Your main character or characters must be fully developed though. If they are not the reader won’t care about them. If she doesn’t care about them and cannot emotionally engage with them, there’s a good chance she won’t read on.

Interestingly, to return to the subject of length for a moment, when I first started writing stories longer than 1000 words I assumed I’d need more characters to get the extra length, but I quickly realised that it wasn’t about adding characters it was about developing the ones I already had. This is one of the most important things I’ve ever learned about short story writing. I later realised it applied to serials and novels as well.

So to summarise, if you are writing a short story of 1000 – 2000 words you probably won’t need more than a couple of main characters and one of them should be main, which takes us nicely on to viewpoint.

Viewpoint

I’m not going to go into the different types of viewpoint at great length here. I will cover those in the viewpoint section (or should I say on the viewpoint shelf). But just in case you’re new to writing, viewpoint simply means whose eyes we are experiencing the story through.

For example, let’s assume we are writing a story about a marriage break up where the wife has had an affair and left her husband. There are three characters in this story: the wife, her lover and the husband. The story might be told through the eyes of any of them, if it is the wife, then she will be the viewpoint character. Not only will we see the action of the story through her eyes, but the story will be coloured by her viewpoint.

It is traditional in a short story to stick to one viewpoint, although you may change if you have a good reason. The viewpoint character also tends to be the main character. There are certain things that should happen to a main character in a short story, one of them being that they should experience some kind of change.

Dialogue

Dialogue is fictional speech. It is very important. It characterises and moves on the plot and gives life to a story. It’s possible to write a short story without it but again you should have a good reason – and by this I mean a reason linked to the story, not just because you don’t fancy the idea of writing dialogue!

When you are working within the very tight framework of a short story, dialogue is even more important. You can, for example, start a short story with dialogue and throw the reader straight into the action and also set up what your story is actually about.

Let’s take the example of the wife, husband, lover story. You might start it like this:

“I’m leaving you, John. I’m sorry, but it has to be like this.” Kathy knew her voice was calm, but inside she was shaking.

“You’re not going anywhere.” He took a step towards her and she was glad the table was between them. “If you think I’m going to let you walk away with that scumbag you’re more of an idiot than I thought.”

This is not particularly subtle, but it’s a swift way of setting up a scene. Already we have a glimpse of the couples’ history as well as what is happening now. Kathy is obviously afraid of her husband and it looks as though she has good reason. You can show a lot of information through dialogue that would take considerably longer in narrative.

Plot

A short story is a snapshot, a glimpse into a character’s life but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t have a plot. Without one it will probably be too slight. A plot is basically a series of events and in a short story it tends to start with the main character experiencing a problem, which by the end he or she will have resolved. There should be some surprises along the way; otherwise you’ll end up with a linear sequence of events. For example, a basic crime story might be: crime is committed, crime is solved. This is not a plot. In order for it to be a plot, there must be surprises along the way.

Maybe the person committing the crime is not who we thought, or maybe we learn along the way their reasons are not selfish but altruistic. Either of these scenarios would turn a sequence of linear events into a plot.

Setting

You won’t have room for reams of description, but you must have a setting. Your characters cannot interact with each other in a vacuum. Setting needs to be skilfully interwoven. To go back to our husband, wife story, the mention of a table indicates that the story is taking place indoors, possibly in a kitchen. Further snippets of setting would need to be given.

Pace and time span

The pace of a short story is swift. There isn’t time for lengthy set up; the reader should be dropped straight into the action, which must be relevant. Then the story will proceed quickly to its conclusion. A short story by its nature will often only cover a short time-span in the life of the character, say an afternoon, or possibly a few days.

Flashback

Just because your story takes place over a short time span doesn’t mean that you can’t bring in past events, via flashback.

Structure

Structure, pace and time-span are linked. For example, let’s assume you’re using a diary structure. You could divide your story into a series of sections, each headed up as a different diary entry. In this way the story can move seamlessly over a longer period of time.

Theme

For me, the theme is the glue that holds the story together. A theme dictates what the story is about. Is it loneliness, revenge, healing? If you know before you begin, then it will help you to stick to the point and only include what is relevant. Theme is a great help when it comes to cutting and editing. It will help you ensure your work is tightly written.

***

This is the end of the extract. If you would like to read more of the Short Story Writer’s Toolshed you can purchase it for your Kindle for £1.99 here.

If you are reading this between 12th and 19th April, 2016 you can get it at a bargain price of 99p. Here.

If you prefer a ‘real’ copy. It is also available in paperback for £4.99, Here.

Happy writing.

Very best wishes

Della xx